|

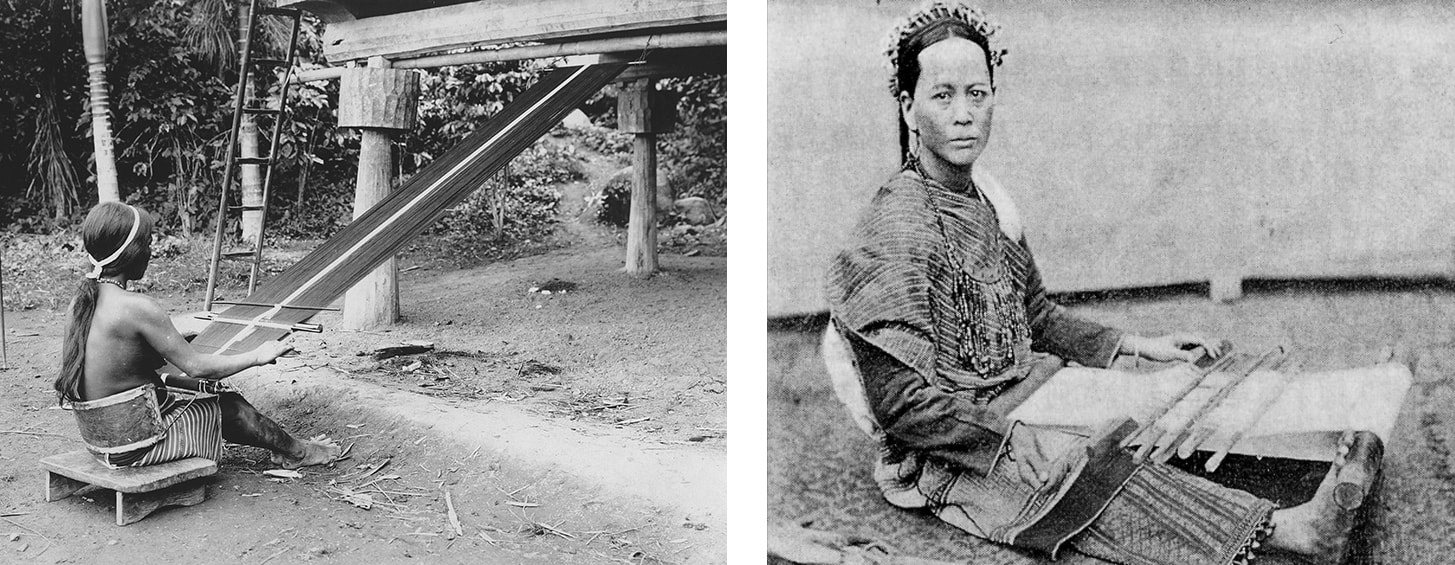

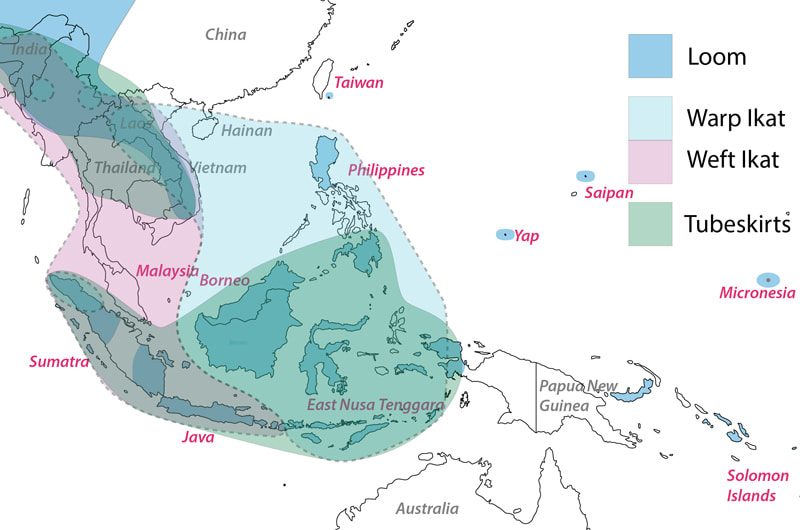

Larena et al’s recent paper “Multiple Migrations to the Philippines during the last 50,000 years” [1] reveals the genetic signatures of at least five waves of migration to the islands. Rather than a single colonization event around 4000 years ago, suggested by the well-known ‘Out of Taiwan’ model, several different groups appear to have journeyed to the northern Philippines between around 15,000 and 8,000 years ago. These migrations pre-date the arrival of agriculture and were presumably coastal-dwelling foragers, who left their genetic signatures in Cordilleran peoples in the north of the islands. The Philippines archipelago is an important staging post for the expansion of the people who are now called Austronesians, who inhabit large parts of the Indonesian and Philippines islands, alongside Austro-Papuan migrants who arrived earlier. In recent years understanding of this migration has been dominated by the ‘Out of Taiwan’ model, which posits that the first representatives of this group journeyed from the southern tip of Taiwan to the northern coast of the Philippines around 4000 years ago, before continuing their migration south and east into other parts of ISEA. Larena et al’s findings don’t mean that the ‘Out of Taiwan’ model of Austronesian expansion is completely wrong, but rather that this particular migration was one amongst many. This shouldn’t come as a surprise. Many elements of present-day Austronesian life, such as the pigs, dogs and chickens that are an integral part of village life, have been shown to have originated directly from the Asian mainland. When I investigated weaving techniques and looms a decade ago, it became clear that these techniques were known to the earliest migrants speaking Malayo-Polynesian (MP) languages, but could not have come from Taiwan [2]. Weaving is deeply embedded in Austronesian culture, made clear by the work of Robert Blust and others, who found cognates for weaving tools and practices in far flung locations across the archipelago. Blust’s reconstruction of proto-Malayo-Polynesian includes a core vocabulary for weaving and textiles, including the verb ‘to weave’ (tenun), terms for the weaver’s sword-beater (balira, baliga, balira), cloth beam (atip, ati, apit, hapit) and a tubeskirt (tapis, tais), amongst others. However, the Malayo-Polynesian loom is different from the one found today amongst aboriginal peoples speaking Austronesian languages on Taiwan. It incorporates an improved warp beam fixing method that is found today in mainland Southeast Asia (MSEA) and the foothills of the Himalayas, mainly amongst Austroasiatic and Tibeto-Burman speakers. Characteristic Malayo-Polynesian techniques such as warp ikat and making tubeskirts are also absent in Taiwan but common in MSEA:  Photos: an Ifugao weaver from the Cordilleras (left) uses a typical Malayo-Polynesian loom with a warp beam (furthest from the weaver) fixed to an external point. She can weave a long and wide cloth on this loom. A Kavalan weaver from Taiwan (right) uses a simpler loom with the warp beam lodged behind her feet. This kind of loom is less versatile, and best suited to shorter, narrower pieces of cloth. The most likely scenario is that migrants from Taiwan arriving in northern Philippines were joined by migrants arriving directly from the Asian mainland, perhaps from several locations, over a period of several thousand years. Some aspects of mainland culture, such as weaving techniques, proved more convenient than the versions from Taiwan, so it was the mainland versions that spread throughout the archipelago.

With hindsight, it was never particularly plausible that all Austronesian migrants came from Taiwan. The Taiwan-Phils sea crossing is a tricky one (if your navigation is not up to scratch you are liable to find yourself in the middle of the Pacific). If seafaring vessels and navigational skills were up to the mainland-Taiwan and Taiwan-Phils crossings, there must surely have been many other easier routes that were regularly navigated at that time. Furthermore, there are no MP languages spoken on Taiwan today, except by the inhabitants of Orchid Island in the far south, who seem to have arrived at their present position relatively recently (they speak a Bashiic language, related to those of the Philippines, and use the Malayo-Polynesian loom, and their material culture is distinctly different from groups living on Taiwan). The Austronesian languages spoken on Taiwan are related to MP, but belong to different branches of the ‘tree’. So, wherever proto-MP originated, it was probably not on Taiwan. This being the case, why does the ‘Out of Taiwan’ model exercise such a powerful hold on collective thinking about Austronesian migrations? It is a ‘good story’ of course, but there are four other reasons that I can think of: 1) Historical accident – the loss of mainland evidence The Asian mainland, in the region of the Yangtse valley and what is now Southern China, was once an ethnically diverse region, probably with diversity that rivalled or exceeded MSEA today. This included the ancestors of Tai-Kadai, Austronesian and Austroasiatic groups. Nearly all of this diversity disappeared within the last 2000 years as a result of the expansion of Han speakers. The descendants of groups who sailed to Taiwan are now completely gone. As a result, Taiwan is now the remaining pocket of deep-time diversity of Austronesian peoples. Inevitably, linguistic and genetic reconstructions point to Taiwan, because they can point nowhere else. This is not evidence for exclusive Taiwan origins, but an artifact created by the loss of mainland evidence. 2) Tectonic circumstances – difficulty of coastal archaeology outside of Taiwan Many of the earliest settlers lived on the coast. But coastal archaeology in ISEA is difficult: key sites are submerged by rising sea levels in the last 10,000 years. In contrast, archaeologists on Taiwan are fortunate. Aside from relatively good funding for their investigations and a long history of archaeological work, they live on an island which is being uplifted at a remarkable rate – between 0.5cm and 1cm a year on many parts of the coast. This means that early coastal settlements are well-documented, whereas in most parts of ISEA archaeological finds are mainly in caves … transient-occupation sites that offer few clues about populations and lifeways. 3) Signal strength Archaeological work is hard, but the ‘signal’ from the early agricultural Neolithic is amongst the easiest to spot, because intensification of land use supported larger populations, who left distinctive stone and pottery tools. The ‘signal’ from early settlers from Taiwan … shouldered adzes, red-slipped pottery … is traceable across ISEA, whereas other groups (such as coastal foragers) are harder to spot. 4) Expansionary languages: winner takes all There are a number of examples of expansionary language groups (Indo-European, Bantu, Austronesian) that have come to dominate large geographical areas. This tendency can give the impression that such expansions were monolithic in character. The genetic evidence tells a different and more complex story. To re-iterate: none of this means that the detailed archaeological work tracing the movements of Neolithic peoples from Taiwan to the Philippines is wrong. That population movement is real. But, as Larena et al have shown, it isn’t the only one. References 1. Multiple migrations to the Philippines during the last 50,000 years. Larena et al Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Mar 2021, 118 (13) e2026132118; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2026132118 2. Buckley, Christopher. "Looms, weaving and the Austronesian expansion." In: Spirits and Ships: Cultural Transfers in Early Monsoon Asia. Singapore: ISEAS Publishing (2017).

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Christopher Buckley

Researcher in cultural transmission and evolution and traditional weaving practices Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed