|

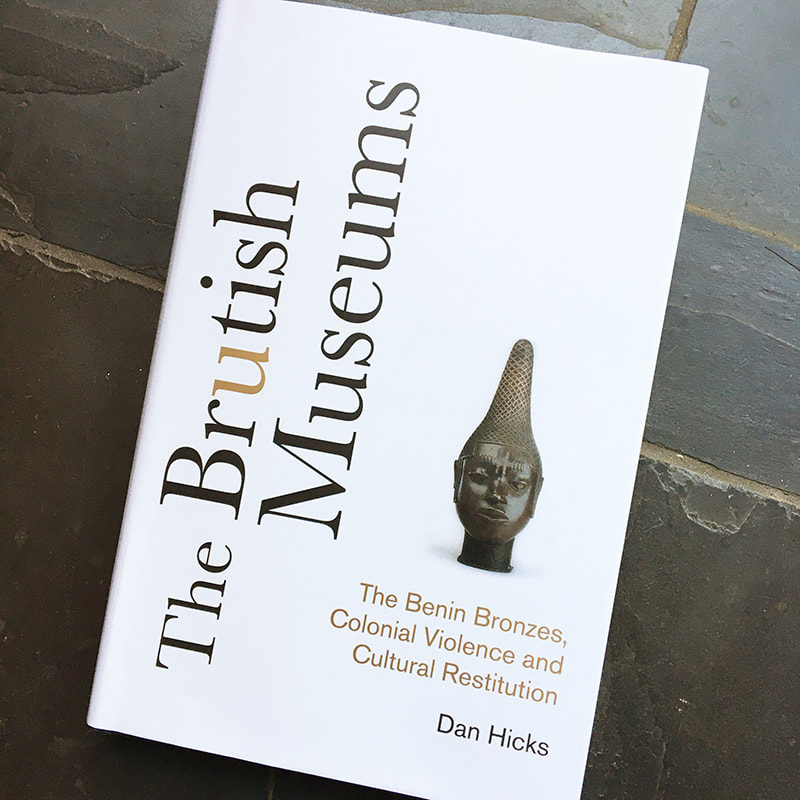

The Brutish Museums: the Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution.

Dan Hicks, Pluto Press, 2020. Dan Hicks is an Oxford Professor and curator of the Pitt Rivers Museum, which is a part of the University there. His book addresses some (very) topical issues and is a must-read for anyone involved with curating or studying ethnographic material. I have a personal interest and enthusiasm for his museum since I remember it well as an undergraduate, and have visited it many times since, the last time around a year and half ago. Prof Hicks’ book discusses the issue of restitution, taking as its starting point the Benin Bronzes, which were looted from the city of Benin (in present-day Nigeria) by the British Army in 1897, then sold to various museums around the world by the victors. He describes the background to commercial and trade-based colonialism that took place in Africa the second half of the 19th century, which focussed on extraction and exploitation rather than settlement, and the events that led up to the planned and premeditated destruction of Benin. The key quote in the book is an anonymous tweet that appeared in 2015 during the ‘Rhodes Must Fall’ campaign at Oxford: The Pitt Rivers Museum is one of the most violent spaces in Oxford (p209) Developing this view, Hicks sees the keeping and displaying of the Benin Bronzes not as a passive or neutral act of ‘curation’, but as a continuation of the violence by which they were obtained. The colonial museum, as conceived in the second half of the 19th century, he views as ‘a weapon, a method and a device for the ideology of white supremacy to legitimize, extend and naturalize new extremes of violence within corporate colonialism’ Concerning his own museum, the Pitt-Rivers, he has this to say: ‘brutish museums like the Pitt Rivers where I work have compounded killings, cultural destructions and thefts with the propaganda of race science, with the normalisation of the display of human cultures in material form. An act of dehumanisation in the face of dispossession lies at the heart of the operation of the brutish museums.’ (p180, emphasis in the original). Hicks makes a clear and (I think) unassailable case for the prompt return of the Benin Bronzes to Nigeria. He nicely skewers the vague notion of a ‘world museum’ that is currently being touted as a defence against retaining loot, as well as the emerging line in ‘decolonisation-spin’, whereby museum administrators hope to deflect difficult questions by camouflaging themselves in decolonisation-speak. It’s time to stop talking and send the objects back, along with the Parthenon marbles. This is not only the right thing to do, it would also send the message that ‘something is actually being done’. The current position of British museums on restitution of the Bronzes is summarised here. There are some encouraging signs, but it sounds as if an opportunity may be missed because of the tendency to stifle progress with committee meetings and ‘due process’. Administrators everywhere live in terror of ‘setting a precedent’. Hicks’ book focusses on the Benin Bronzes. He has little to say about the other 99.99% of other objects in ethnographic museums, beyond providing a tentative classification in the ‘Afterword’ of his book. Few objects have the kind of detailed accounts of how they were obtained that the Benin items have. Anyone who has been into the storeroom of a provincial museum knows what reality looks like: something like your granny’s attic, but less systematic. As a teenager I spent a happy summer helping to sort out the mess at the museum near my home: magic lantern slides heaped on top of African masks. None of it labelled. This is the real problem faced by museum curators: chaos, quantity, the absence of information and a lack of resources. Hicks projects the notion of ‘violence’ backwards to the founding of the ethnographic museums, arguing that ‘violence’ was inherent in their founding. Is this supported by what we know of the founding of these museums? Take Hicks’ own museum, the Pitt-Rivers, as an example. The Oxford Pitt-Rivers began as the private collection of a wealthy man: Augustus Lane Fox Pitt-Rivers. We are fortunate to have great documentation of the early history of the museum online, assembled by Hicks’ colleagues, a primary source that includes the correspondence of its founder with the University authorities, and a wealth of other documents: https://web.prm.ox.ac.uk/sma/index.php/primary-documents/primary-documents-pitt-rivers-museum.html The picture that emerges from the correspondence of Pitt-Rivers is that of an avid collector, devoted to promulgating his ideas about the evolution of material culture. In a letter to E B Tylor (who would become the museum’s first curator) he explains his desire ‘to illustrate the development that has taken place in the branches of human culture which cannot be so arranged in sequence because the links are lost and the successive ideas through which progress has been effected have never been embodied in material forms’ https://web.prm.ox.ac.uk/rpr/index.php/primary-documents-index/15-founding-collection-1850-1900/420-pr-to-eb-tylor-571883.html There’s little about colonialism or empire here, this is a man who was driven by an idea. He also held strong (establishment) political views, and saw his collections as a kind of moral and political lesson, though not the one that you might expect from Hicks’ account. Pitt-Rivers, like many of his contemporaries in the British upper classes, feared revolution. This concern seems quaint today, but it was real at the time, and not far off the mark, as subsequent events in Europe showed. Pitt-Rivers thought his displays of incremental change in material culture would impress the virtues of gradual change on museum visitors, making them less likely (presumably) to rise up and slaughter their oppressors. This seems to have been a leading theme in his second museum at Farnham in Dorset, where he was a prominent landowner. Still, contemporary ethnographic museums must change, as Hicks says. The harder part of the question is ‘how’. Once the stolen items (at least those that can be identified) have been returned, what of the rest of the ‘stuff’? It’s harder to discern in his book exactly what Hicks wants. He likes the idea of an anthropological museum, but what kind? He offers the following vision: ‘Our purpose must be to redefine the purpose of the anthropological museum. I propose thinking about this as a move away from being a space of representation and towards what Hannah Arendt called ‘a space of appearance’ – in which curatorial authority is actively diminished and decentered while their expert knowledge of the collections is invested in and opened up to the world’ (p36). I’m not sure what a ‘space of representation’ is, but opening up to the world is surely a good idea. The challenge is to make some kind of sense out of the exotic jumble of objects that makes up the Pitt-Rivers. Ironically, the museum that began as a museum of ideas has degenerated into a cabinet of curiosities, encased in gloom after the glass roof was boarded up to protect the exhibits from damage from sunlight. Objects are still grouped by type, but there is little clue as to why this might be important. The ongoing decolonising efforts of the museum staff are described on this web page. I haven’t seen them in person yet: https://www.prm.ox.ac.uk/critical-changes From a personal perspective, I think there is much that could be celebrated at the Pitt-Rivers. The museum’s founder and its first two curators, Edward Tylor and Henry Balfour, are nexus and point of origin of many key ideas in contemporary archaeology and anthropology. In archaeology the notions of typology, seriation, systematic excavation have their origins here. In anthropology, the study of culture, notions of change, phylogenies, convergence and rediscovery of similar solutions in different parts of the world. In heritage management, the idea of protecting ancient monuments and archeological sites. In museology, the use of models and sectional displays (by Pitt-Rivers) to explain and inform. The challenge at the Pitt-Rivers is to provide meaning to a disparate group of material objects, and to explain the very existence of the collection, if it is to regain some kind of purpose. Marvelling at diversity was not enough in the past and will never be sufficient. The ideas I have mentioned provide structure and unity to the collection, and by implication, to humanity.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Christopher Buckley

Researcher in cultural transmission and evolution and traditional weaving practices Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed